Tags

Afghanistan, corruption, culture, daily life, GIRoA, government, government effectiveness, humor, politics, stability, vulnerability

So, yes, we get the idea that Afghanistan is kind of a corrupt place. But really, with the lawlessness and the massive rift between the political elite and everyone else, what else would we expect?

I was part of a meeting that took place in a small village in Paktiya Province. It had been pre-arranged, so all of the village elders came out in force, as did every other male in the village, from age 5 to 85. The village was at the top of a small hill that had a cliff that overlooked the nearby river valley. In fact, it may have looked an awful lot like the village in the banner picture of this blog. As we walked up the goat-trails (easier said than done while in full body armor), the men laid out a giant cloth on the ground and a bunch of padded cushions that were upholstered in red fabric that read, “Japan!”

After the official meeting, we broke into small groups to just chat. I started talking with a man in his early 30s who complained bitterly of politicians doing nothing but hoarding all sorts of money for themselves, playing favorites with projects, and giving public jobs to their family members. Since there was an election coming up, I asked him why he didn’t run for office and try to change things.

He gave me a grin that was somehow proud and sheepish at the same time.

“Because I’d be even worse.”

I had to laugh and he laughed along with me.

Corruption not only happens, it’s expected. But why? Because power corrupts?

Well, partially. People are people, after all, whatever culture we may have been raised in. But there are some particularities of Afghanistan that make what we would call corruption a good idea.

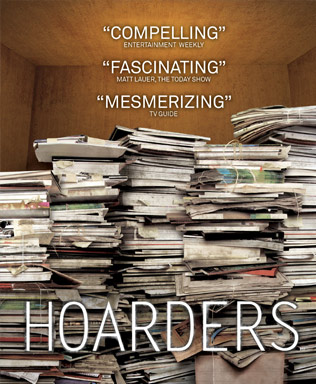

First is the expectation of violence. When you’ve lived through 30 years of war and then combine that with a couple thousand years’ worth of empires marauding through your territory, stability is not exactly the status quo. You expect chaos. You develop a mentality of preparing for it. So to protect yourself and your family, you gather all the resources you can and hold onto them (not unlike zombie apocalypse preparedness). In other words, you become a hoarder par excellence.

And if you happen to get into a lucrative position, you take advantage of that and get as much as you can, be it a well in your backyard built by the Americans or a new road to your village or a whole bunch of jobs for your family so you can collectively stockpile as much money as humanly possible before this government goes the way of all the ones before it.

There’s another element to this, though too. Across the Middle East and Central Asia, honor and shame play a major part in society. Sure, honor is important to us all, but in these areas, honor is much more tied up in the family than it is in the US or Europe. If my brother or cousin or third cousin twice removed does something dishonorable, it doesn’t really reflect on me, but if I live in Afghanistan, my cousin’s shame is my shame. And shame isn’t just about being looked down on, but think Scarlet Letter levels of excommunication. If I am shamed, basic things like getting married, getting a job, etc. are jeopardized.

So to avoid situations like that, you work really hard to earn honor and prestige. Across the Mid East/Asia region there are various formal and informal honor codes that create systems for people to earn honor. Many are pretty similar across countries. Hospitality is a big element of them (to refuse it is to seriously insult your host). Another is protecting guests in your home as fiercely as if they were your family. A third is providing sanctuary, even to your worst enemy.

And charity is a big one (it’s actually a requirement in Islam). Charity is especially important if you are a powerful or wealthy person. If you have money (or tons of cropland or goats or whatever), you earn immense honor by sharing your wealth, most particularly with your extended family. It earns you loyalty, respect, prestige. It can make you into a Big Man/tribal leader/warlord/sheikh/chieftain/etc. It’s a pretty common pattern around the world. A leader is someone who shares his wealth.

It’s not so different in our culture, really. Every time I go to visit the undisputed matriarch of my family (my little Italian grandmother), she presses $20 into my hand. She has done so since before I can remember and it doesn’t matter that I’m now over 30 with an income that’s probably three times her retirement pay. I wouldn’t dream of refusing it. It’s what she does, a point of pride and, yes, honor. (Besides, if there’s any doubt as to where I get my stubbornness, let me assure you, it’s that side of the family.)

Where it becomes problematic in Afghanistan is when people who live by that ideal get into political power. Taking care of their extended family via what we would call favoritism and nepotism is, in their eyes, the right thing to do. You take care of your own. Period. It just happens that when you do that with public funds and positions, people tend to get a little persnickety about it. While admitting that they would do the exact same thing.

Don’t get me wrong, by no means does everyone do this. There are a lot of Afghans who believe the political system should be free of this kind of thing. They don’t play favorites, they don’t succumb to nepotism, they push hard for anti-corruption investigations and convictions. There just also happen to be a lot of people who have decided to do the best they can for themselves. And for those guys, when they help their people out, they consider it to be the smart, honorable, expected thing to do.

It only becomes “corruption” when you’re the one not getting a cut.

Doc…enjoyed this article very much.

Extending a warm Holiday Greetings to you and your family…all of them around the world.

Thanks Doug and the same to you!

Don’t worry. It’s gonna get much better when we (NATO, the international community or what we used to call the free Western world) all leave in, around or after 2014 because the money will leave with us.

Maybe people in Afghanistan had a mindset which we might call “corruption”. As you say, after 30 years of (civil) war, we can’t blame people for looking after their own instead of believing in state institutions, especially when they still remember the guys who now run these institutions from the time of the civil war. – But this mindset only became a problem of endemic corruption when we poured in billions of $ into a country which had almost no economy. We now contribute around 97% of the Afghan GDP (http://andreasmoser.wordpress.com/2011/11/26/the-afghan-economy-in-numbers/ ). Such an enormous influx of sudden money, seemingly unlimited and largely unconditional of course leads to corruption.

A really great article, but I had to respond to this comment…Seriously? Not only are you completely off base, but the fact that you saw this as a great opportunity to denigrate the United States is even more interesting.

Lol.

I don’t see “United States” or “US” in his comment. That must be denigrating indeed.

Agreed, the financial situation is a major source of mess. It was always a little depressing watching my tax dollars disappearing into someone else’s project. What kept me sane was every now and again watching the final product (which cost 1/10th of the price we paid) be something worth paying for.

Very well written! Your words make it a lot easier for this (average) American to understand the workings of this foreign/difficult culture a little better.

Thanks, Karen. That’s what I was hoping to do! 🙂

Karen expresses my thoughts very well. Well done!

A fascinating perspective on a tense situation. There are many people in the world that believe in themselves first as a manner not of selfishness but of presevation of self. Who doesn’t want the best for thier families? Who doesn’t want a life that is comfortable and secure? There are plenty of americans who would do the very same thing and there are many in our own government. So these people are really not so different from us.

Human nature being what it is (wherever in the world you live) I accept that you can expect and even understand corruption. Excusing it and justifying it is another thing. Your last paragraphs seem to me to be contradictory. You say that ‘There are a lot of Afghans who believe the political system should be free of nepotism [and that] they push for anti-corruption. Yet you conclude that ‘It only becomes “corruption” when you’re not the one not getting a cut.’

Asian cultures from China to India to Egypt have been this way for centuries and maybe thousands of years. It is a way of life and maybe the people that complain about it the most are just jealous that they are not as successful of a crook.

The region you mention also represents collective cultures compared to most of Europe and North American including the US that are individualist cultures, and this may also have something to do with what you have described.

What is acceptable in one culture may not be acceptable in another.

Very true about the individualist/collectivist culture. It’s all about the connections…though I’d say the US and Europe have been more collectivist in the past. Not as much as Asian and Middle Eastern (and African too, often), but more so than now.

I think the US was more of a collectivist culture when the majority of people lived in rural America. As the country industrialized and migrated to urban areas, that started to change. I also suspect that those changes toward individualism accelerated starting in the 1960s due to the self-esteem movement where the focus shifted heavily on the individual away from the family.

Very intersting article, however, I fail to see the difference within the U.S., particularly the political power piece.

I had similar thoughts, but it might be fair to say that they hide it more? It’s a behavior that (most of) society in the West shuns after all.

Definitely…I actually would trade stories with Afghans about examples of corruption in America and they found it hilarious. One actually said to me, “Afghan politicians are better because at least they’re honest about being corrupt.”

Well said. Just like in Washington, DC, where many of the politicians are the some of the most corrupt people in the US. Thank you for the insight. Happy New Year to you.

Rob

There’s something different about corruption in Washington though. Maybe it’s less…open? Less prominent?

Thanks Rob, and a Happy New Year to you too!

Interesting.

Thanks for such an insightful perspective, and congratulations on being Freshly Pressed! Stay safe…

Thanks very much!

I loved this article and how it looked at corruption and what it symbolises. I enjoyed the little bit about the Matriarch, she sounds very stubborn!

Haha, thanks, she’s actually very proud of the fact that she got mentioned for being so stubborn. 🙂

No matter how it is justified or excused, people always play favours. After all, to consolidate our power, and to increase it, we need to entrust people whom we can trust with it (thus twice the “trust”). The form you are portraying in your post is tribalism in its purest form. In the West we have different methods to determine who is trustworthy, but the game is the same (e.g. skull and bones fraternity). Remember this proverb: It’s not important what you know, but who you know

Congrats on being freshly pressed!

I agree…we tend to be more process than personal trust oriented here, but the vetting is still important. I love that the Arabs have a word for what they do…”wasta”

And thanks!

Very nice that you are concern about the corruption in Afganistan but let’s take care of business here at home before teaching everybody else in the World how to live.How about that?

Haha, if only we could be so lucky. Something tells me it’s not an easy problem to solve anywhere. 🙂

I’d argue that, as you point out, the problem isn’t corruption as defined by the west but rather corruption that is glaringly unseemly. Very interesting post, thoroughly enjoyed it.

Thanks, I’m glad you liked it. I think your idea is exactly at the heart of this. What “corruption” means can vary, but whenever someone uses the term, it’s always bad.

In a lawless society any measure to ensure your next day’s meal seems legitimate. Corruption would end when people will believe in their institutions and system of government. With no clear picture of their future, being governed by a puppet government limited to certain areas and foreign forces haggling around; what else would you expect from an Afghan?

It definitely has a logic in the light, I agree. It might not be a logic we like, but it is a logic. Thanks for the comment!

Corruption is just rife 😦 http://socialanthropologyblog.wordpress.com/2012/12/29/the-difference-between-capitalism-and-communism/

Unfortunately so, it seems. Humans seem to only like playing fair when it’s by our own rules.

Corruption grows in the dark. An open inquiry means that the tide is turning against corruption, not the contrary. You forget some murders. There has been a series of murders in the Montreal metropolitan area during the time the commission was broadcast and reported on. This may be a coincidence, or not.

what do you think about the world’s biggest corrupted country ” india”

I think India definitely has a lot of problems, a lot of different economic, social, cultural and political pressures working against it. You could probably write whole books on it. What do you think?

Reblogged this on Bored American Tribune. and commented:

— J.W.

I feel for your country. It is so much like the Philippines yet we are of Spanish influence.

Very good effort. Afterwards, I thought to myself that your words were far more better reading than any of a lot of what one can find in media outlets. Plus, you made me smile. Well done on making freshly pressed.

Thanks very much! That means a lot to hear. 🙂 Have a Happy New Year!

Unfortunately corruption is present everywhere, and the poorer the place the more obvious it is.

True…I think many of the richer countries get that much better at hiding it.

corruption has always been a major problems especially in the war torn country as like Afghanistan, where from bottom to top, one can easily discern the termite of corruption diffused fully deep beneath the very fabric of this country. It is just because of this corruption which is a hampering it from growing into a sovereign state or country. Neighboring the country Pakistan which is also a sign and symbol of prestigious corrupt public mechanism which has really seeped inside the pores of every social norms and values, is really very much resembling the worst scenario of plundering and carnage of public resources across both the countries.

Good point on Pakistan also being a troubled place and a lot of that feeding back and forth across the border. I wish there was an easy solution.

thanks, i hope so.

Really interesting post, not so different to how the political system works here in Ireland; promise the world to get into power and then hoard as much money and as many jobs for your friends and family as possible in the time that you’re in power.

Thanks for sharing 🙂

Rohan.

My pleasure, glad you enjoyed it. It’s always a little shocking to look at another system and see a reflection of your own… 🙂

An enlightening view into a world few of us really understand.

Thanks for replying, and I’m glad you think so.

You book should be fascinating! If you need an editor or ghostwriter, shoot me an email; twice well-published.

Thanks very much and I will be in touch when I get that far…I don’t suppose you could recommend any agents as well?

Great Article. Have a safe and happy holiday and ring in the new year with the best at heart.

Pratibha

Thank you very much and a very Happy New Year to you too!

Thanks for this article. It’s great to have someone’s perspective that’s actually close up. I personally think that the world’s problems are just to big for humans – period. Yeah, we should do what we can to stave the crazies off, but in the end, it’s gonna take more than human efforts. Great job.

Thanks very much. And it may make me a wide-eyed idealist, but I think there’s always room for hope.

Pingback: Corruption! It’s How We Roll! « timothyimholt

I enjoyed reading this. It shows that viewing something with empathy is not the same as approving of it. We should try to understand problems like corruption before we try to solve them, or assume that people in another culture approach life the way we do. Anyone who’s interested in corruption as an issue should look up the TraCCC center at George Mason University.

Thanks Kelli, I really liked the way you put that. It encapsulates what I try to do with all my research in a nutshell. Will definitely check out the TraCCC center.

You have given us some invaluable insight here, thanks.

It is true that most corrupt politicians do not think of themselves as corrupt, it’s just how things are done. The all-to-human urge to grease palms, to cut in line, to get that ‘edge on the other guy, will never go away.

I couldn’t agree more. We all try to get an edge and none of us are the bad guys in our own eyes. Thanks for reading!

Thanks for this. It’s good to read something perceived and written down by an open mind about this issue.

Thanks! And thanks for your comments on some of the other comments. Very insightful.

My pleasure.

Great article. My brother in law went there in the war (British soldier) and he said roughly the same as you. There is no way we can or should change their culture. That will come from Afghans themselves. As for corrupt politicians, you only have to look in our own back yards – a descipable lot.

Agree on all counts. Corruption is everywhere and change, in any form, must always come from inside. Otherwise they just wait until we leave and go back to what they were doing before–or even go more extreme out of anger and a feeling of repression.

Corruption isn’t just a problem of that country at all, but a worldwide epidemic. I’m sick of reading and hearing about outrages all over the world, especially in my country, Spain. It is suffering a huge economical crisis and despite it politicians and big companies are getting more and more corrupted in a disgraceful way. I know Spain isn’t the most corrupted country in the world so… I “can’t wait” to know about the rest.

I’ve had the chance to go to Spain and thought it was a great place. But you’re right, when things are falling apart is when you can often see just how corrupt the system is. I guess all we can do is hope for the best and work in our own small ways to make it better. And then hope some more. 🙂

Yes… I think the real problem is that the people’s awareness doesn’t last when everything is ok. As you say, when all is falling apart the situation is another, people are too burnout, so they don’t forgive any bad act.

There is a ton of corruption in Afghanistan caused completely by the heroin trade. The Karzai government there which we support is definitely in on it, the justice system is a court of revolving doors run by corrupt bureaucrats who take money and let people who are by chance caught go. If you legalize heroin you take away the power of the insurgency completely. With all the turmoil caused by the illegality of heroin the children of the country suffer the most. At http://www.playgroundentertainmentgroup.com we try and show kids through sports a better way of doing things.

I most definitely agree. I figured the drug trade angle was a little too much to go into on this blog, but you’re absolutely right that heroin is a giant triangle of insurgent and government corruption alike. I will be checking out your website. Thanks!

“It only becomes “corruption” when you’re the one not getting a cut.”

And since I do not get a cut from the Chicago machine, they are truly corrupt ….

😉

Be good, safe, and come home. We are praying for you.

And yes, I blog and tweet to those in charge to bring ya’ll home soon.

Ghost.

Haha, I feel that way about most of my government. Glad you appreciate the somewhat snarky sense of humor though. 🙂 Happy New Year!

PS, Happy New Year, Happy Orthodox Christmas (& they taught me the Commies were such bad people …. ), and Happy Orthodox New Year. Great having a MONTH of actual celebration.

8 years as a Non-Comm. Leader of men and women.

Of course, I even appreciate my enemies. Snarky or not.

🙂

And you should visit Vienna for Christmas some time …. Italy just was not as festive – economic problems maybe?

We do pray for you. We pray ya’ll come home. We realize you won’t come home four years ago like we were promised. But, you volunteered so that makes it better, right?

🙂

I really wanted to campaign for president. But, my body is really torn up. Physical Therapist Assistant at Bragg damaged the spinal cord, experimental injections killed (desiccated) a disk. Two surgeries to stabilize. (fusions) And now, I realized I do have limitations.

Stay healthy!

Be safe.

And we are praying until all come home, not just until the media mafia says everyone came home.

Ghost.

You did a terrific job of explaining the clannish nature of the Middle East and Afghanistan(which may or not be “Middle Eastern” depending on how you define it but the cultures are similar), and how it breeds corruption, among other things. It also undermines nation-building. I really enjoyed how you mentioned the Afghan man who complained about the ultra-corrupt politicians in his country, yet believed he would be even worse if he had their power. Even in less corrupt parts of the world, there is no reason to believe the biggest complainers of corruption would be any less corrupt if they held high office.

This is one of the reasons I don’t think the Middle East or Afghanistan(I realize Afghans are not Arabs) will get much better due to the Arab Revolutions, since it is simply one corrupt group of people replacing another corrupt group. I know that sounds pessimistic, but I am approaching this as a realist.

Thanks very much. Speaking of the corrupt replacing the corrupt…have you watched any of a youtube series called “Top Goon”? It’s a satirical puppet show that anonymous Syrians started filming at the start of the conflict there. Season 1, Episode 7 depicts a senior general saying something similar–that all the top people in Syria will do if the protesters win is change their image and wind up right back at the top. Worth checking out if you get the chance.

I now have a totally new understanding of the Afghan psyche. Thanks for a very informative article..

My pleasure, glad it provided some insight!

Hey Doc, when will you be stateside? Lectures? Relaxing? Where do you see yourself in five years? You are a most teaching, and knowledgeable curious woman providing insightful observations most of us would never discover. I hope you will keep your fans ( me ) informed along the way.

Doug

I am actually Stateside now. It’s a whole lot safer for the people I talked to in Afghanistan if I waited until after I returned home before blogging about them. I’m currently teaching and have done some guest lectures here and there. Am always happy to share thoughts and ideas.

And in five years? I’d love to still be doing research along these lines, maybe somewhere more forgiving like Africa (haha), or getting into more of the foreign policy realm to help apply these lessons to the bigger pictures decisions we make. And in 20 years? Secretary of State!

Great post however , I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this subject?

I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Cheers!

Well, I did two other posts prior to this one on corruption in Afghanistan, but is there something you’d like to know a bit more specifically about?

Excellent excellent post. I definitely will be a daily visitor to your site, beginning now. I feel we need to be out of Afghanistan—the sooner the better. I know this may seem callus but ten years of lives lost, both American soldiers and Afghan civilian is enough. The political and governmental corruption, as you mention, will not allow any form of democracy. Tribal values are hard to replace. It will never happen.

Thanks! Afghanistan is definitely an odd mix of westernized and tribal…the cities and some areas can be really similar to our own way of doing things, but so much of it is just not there yet. And it’s tough to say what the best way to leave was–the reason I titled this blog Marking Time is because that’s what everyone is doing so they can see how it will all turn out once we go. But there are little victories that make a big difference too. It’s not easy and I’m glad it’s not my decision to make.

Re : contructiveconservative, don’t see anything constructive in your comment . The article was written I believe to provide a perspective , from someone who has “walked in another”s shoes “. And with that perspective to try and find a workable answer.

Thanks for the article. I have come across a couple of WordPress accounts discussing the Afghan way of life, and it has made me want to learn more.

I agree strongly with you about how strongly the embrace of ‘the way things are’ is, showing it is not that different in Afghanistan than in the West. Family looks after family, but it becomes a greater issue as the money involved increases. Having the likes of the Achaemenids, Alexander the Great, the Sassanids, and the proponents of Islam seize power over their long history would instil a sense of providing for their family’s future in any way possible.

Thanks again, and a Happy New Year to you =)

Haha, very true, there is a long, long history of people coming and going in this area. It’s got to be a strange feeling just watching empire after empire come, try to instill their ways, and then leave again.

Happy New Year to you too!

Very interesting! Really enjoyed reading that, great to get some insight into other cultures.

Thanks very much, glad you liked it!

We naturally think that the social structure of other cultures are similar to our own but it is not true. In Afghanistan, corruption is what is expected. How can we change the expectation of the entire Afghan population?

Haha, if you figure out a way, please let me know. Really, though, we can’t and shouldn’t. If change doesn’t come from the people themselves, it will never stick.

There used to be a joke here in the U.S. that white collar criminals didn’t go to jail, they went to Texas to be congressmen and senators. Now they come to Illinois to be governors. Corruption and panic are everywhere. If it’s this bad in IL, I can’t imagine what it’s like in Afghanistan!

I wish I’d known that joke while I was in Afghanistan…they would have loved it! The thing is, I think most of them are kind of resigned to the whole thing. It’s easier than getting mad about it.

Excellent viewpoint on this. The candidness of these cultures can set us back a bit. One thing that came to mind when reading this, is the fact that if one person works hard to make change or be successful why would they share with some people? What did they do to earn a piece of the pie? I think corruption also includes an inherent feeling of entitlement. It’s no fun to be ‘bird-dogged’ by others while they wait for you to bring home the real bacon.

Interesting thought I hadn’t necessarily considered. I like that, thanks.

Thanks MT. Your post’s very educational and full of culture aspects I was not aware of.

We all run around making judgements and adverse comments on many of these people, but we do this without understanding their ways and what runs just below the surface.

Maybe if we tried to learn a bit more about their culture, we might not be so harsh in our comments and opinions. We might just be a bit more understanding.

Cheers

Mick

I agree, it’s why I love being an anthropologist. Of course, helping them understand out culture (they base a lot of their assumption about us on movies, so think we’re all incredibly beautiful and extremely violent) was just as important and just as complicated.

Wow it’s looks like complicated case there, but option to leave them decide what they want still better…thx

Luxury Villas in Seminyak

True, because in the end, that’s what they’ll work for anyway.

You hit the nail on the head when talking about honor and shame. In America we take people who have little of either quality make them famous and stick them on MTV for our kids to see. It is no wonder why kids act the way they do anymore! We are showing them this kind of behavior is what is acceptable and rewarded.

It’s amazing what you internalize when you’re young. But as much as I deplore MTV culture (and believe me, I do), when I see the rape culture of India, all I can think is that at least America is better than that. There’s got to be a happy medium somewhere, but I have no idea how we get there.

Corruption, for the reasons you describe above, happens here too. Our government rationalizes taking from one to give to another when they believe they are doing it for the common good. Soon, our country will lurch from one regime to another.

defending-ourselves-from-irs-tax-abuse.com

Haha, regime, political party, tomato tomato (that looks odd written out) I feel somedays

Just discovered your blog and read this post. Very interesting. I visited Afghanistan only very briefly 4 times, once from Iran in 1972 when the king was still there and 3 times with mujahideen from Pakistan in the 1980s. I like this post because it seems a really honest account of your experience, and I want to read a lot more of what you have written and are going to write about Afghanistan. – If you are interested I have some pictures from my 1980s trips to Afghanistan on Flickr/photos under the name “erwinlux.” They are free for anyone to use.

Wow, that’s pretty amazing. I would love to hear your stories on it sometime. And I will definitely take a look at your pictures. I can only imagine how much it has changed since then.

It is interesting how corrupt we are becoming in many cultures. I hope things turn around soon! Don’t you?

I certainly hope so!

Have a great New Year! http://www.segmation.wordpress.com

Coming from an Arab background, the culture is definitely about family first–to everyone’s face. As you said, this is to maintain honor and dignity. For years, we could not get my mother the substance abuse help she needed because my father refused to believe in the degradation he would have to face.

Also, in the middle east, there are two types of people: the workers and the moochers. Behind each others backs, people are constantly trying to supersede the other, especially the moochers upon the workers seeing it as “charity.” It is definitely human nature but I can see many of the similarities in what you are saying from personal experience.

Lastly, there is an interesting dichotomy behind bringing religion into the issue of corruption in that region. Where it is so predominately Muslim, there is so much violence. Why? In Islam, we call each other brothers & sisters… and it says in the Qur’an when referring to the story of Cain and Abel that killing one person is like killing all of humanity. Blood related or not, it is a sin to kill, especially for power or jealously, if one believes in Abrahamic religious texts.

Great read. I’m glad I pressed the Freshly Pressed button! Happy New Year!

Thanks for your feedback! I always feel a bit reassured when people from similar regions and cultural backgrounds as those that I study have similar ideas to mine. I’ve also heard similar stories as your parents about all sorts of substance abuse and mental illnesses. It’s heartbreaking. I hope your parents made it through in the end! And thank you again for sharing!

Really straight forward post, thanks for sharing. Congrats on being Freshly Pressed!

Thank you and glad you enjoyed it!

Reblogged this on Isa Ibrahim.

Widespread corruption is intolerable especially if you are from an industrialized country. The elements you describe such as extended family and gift giving are a common denominator in every developing country (read country with extensive corruption). The underlying reason for corruption is public institutions that are weaker than social ones. When public institutions mature enough (with economic growth), they can replace the welfare/corruption of social networks. Thats really all it is.

Have just finished ‘a thousand splendid suns’ by Khalid Hosseini. A gripping, human and beautiful story of Afghanistan through three decades. Strongly recommend it.

I’ve read Hosseini’s work as well and agree that it’s great.

I also agree quite a bit on the social vs. public institution idea. I think there may be different social systems that create more or less degrees of what we would call corruption and public institutions in places like this are often undermined by the social ones (I actually have an article on justice systems facing that problem in Military Review I’d be interested in your feedback on). But overall, as long as the public system is unstable and illegitimate for whatever reason, people will take what they can get from it and continue their own way.

Happy New Years Doc’!

From up north ….

Happy New Year to you too! Stay warm!

Reblogged this on squarely33.

A superb piece, so well-written and eminently factual.I really do like that you caught the humour of Afghans as well, that self-mockery which is very much a feature of their character and culture – to those they trust.

Hopefully India and Iran are going to be able to help Afghanistan stabilise itself over the medium-term, as contentious as that may sound, but as neighbours there have clear imputes to do so. And Pakistan’s ISI influence has been nothing short of horrendous.

Wonderful article, again. Thank you.

Glad you enjoyed it. And I agree, that sly, absurd and self-aware humor was one of my favorite things about Afghans.

How will India and Iran help? Curious.

Well, India and Iran are a tricky kettle of fish. I’ve seen Indian companies being involved in big reconstruction projects and there are partnership and friendship agreements between the two, but practically speaking, they’re pretty hands-off as a country at this point. Mainly, I think to avoid further antagonizing Pakistan, and because of all their own problems internally. So they’re less of an influence and more of a background presence that lurks behind the whole Pakistan issue.

Iran…well, they have a growing surreptitious influence. They’ve been pouring a lot of money into mosques and schools and there are a lot of Afghan refugees in Iran. Afghanistan also does a lot of importing from Iran. However, a lot of it has a sectarian-political angle to it, and while Afghanistan has made some efforts to court it’s 20% or so Shi’a population, most of them are pretty Sunni. Where Iran might help is in subtly challenging the Taliban in any bids for power they make, since the Deobandi Taliban have no love at all for Shi’a.

But right now, I’d say Iran’s focus is much more on Syria, so really, neither India or Iran is putting a whole lot of thought into Afghanistan. A few years from now, they may step up, but really, Pakistan is really going to be the key player in the short- to medium-term. What do you think?

Haha, there’s a rant. You may have just inspired me to do a blog on the whole Pakistan issue, though. 🙂

I appreciate your comments re: India and Iran.

A great inclusion of Honor Shame mentality. I logged years on another front, pastoring a local church. Honor Shame is a code of operation which dictates so much in that setting, and most people have no idea how much it compels.

Good writing. Thanks.

Thanks very much and I’d be interested someday in seeing how your experiences of honor/shame in a church group were similar.

Reblogged this on Bill's Blog and commented:

Corruption! It’s How We Roll!

I enjoyed this In-Country Viewpoint

I have argued repeatedly that there is so much corruption amongst humans that it is morals and ethics that are actually the deviation. Things like that live well outside the norm. I’m currently working on a societal system that recognizes and plays on this basic trait of humanity but I keep cheating while developing it. Maybe someday.

Hmm, sounds like morals are about like common sense…not so common? 🙂

changed the way i see the world

Thanks!

Doc, high five on this great post and thanks for not using the term Haji.

Haha, thanks. I try not to, unless it’s satirical in nature. Or literally someone who’s been on Hajj. 🙂

Reblogged this on Oyia Brown.

Reblogged this on Anything Interesting on WordPress.

Great post. Fascinating cultural details which were new information to me. Here in Chicago, a former mayor and his mayor father were often accused of nepotism (maybe done in the same spirit you describe of some Afghanis). Congrats on being FP!

Haha, I’ve heard that a lot about Chicago…hey, maybe it’s just a cultural legacy of looking out for #1! Thanks and glad you enjoyed it!

Doc I would like to offer you a virtual high five and a virtual lifetime supply of Ben & Jerry’s cookie dough ice cream. That’s just how awesome this post was.

Quick question: Are you a writer? Because this is some great novel material and because you’ve lived it-thanks for your service, by the way- you could really make it come to life.

Done and done! Haha, I am probably pretty corrupt myself when it comes to ice cream bribes. As for being a writer, I’m working on a non-fiction book right now that sort of uses the same idea of short stories, but with an overarching commentary about the war effort itself. It’s mostly done…just finding a publisher is the tricky bit, but I’m trying!

True, very true. It is said that cheating is just part of business, getting caught means you were lazy or unlucky. My experiences in the Middle East mirror those you mentioned here.

Best wishes for you and yours.

Thanks very much. One of the endemic problems of the region, I suppose. And all the best to you and yours!

It’s actually honour versus horror – i.e. to say the common men versus politicians. Unfortunate that it’s the common men who vote, support and make politicians. Travesty…isn’t it?

Honor versus horror…I like that image. And not only do we vote, support and make politicians, but if power corrupts, we might be just as bad too. Not so different from the Afghans in some ways.

Only difference in our politicians and theirs, ours wear suits and ties and theirs don’t. And, the dollar amounts here is high enough that is makes it respectable to be a thief, only we call them Senators and Representatives.

A good post and Afghans certainly take our ideas of corruption to a new level. But I question the whole honor idea. My time in Afghanistan didn’t see much honor, or at least a version recognized in the west. Then again I suppose it is much like the honor amongst gangs around the world, easily imposed, quickly adjudicated and very violent. It seems most often against ones one relatives or clan. I think honor is often just an excuse for power.

Of course passing around millions to the favored of the week didn’t help the situation. However honor in the west is also hard to find, amongst the elite anyway.

Stay safe.

I suppose at the heart of it is that the idea of honor means different things to different cultures. (And individuals too, though I agree with you there that there are a whole lot of those without much of it these days). I think you’re right that gang or Mafia honor is probably the closest we get to Afghan honor–family first above all else, violence acceptable, loyalty to the people who provide for you and your protection, etc. At least now. The old Hatfields and McCoy’s thing was about a certain honor, so I think that sort of thing is in our past too (short-term vengeance is about anger, long-term vengeance usually has an “honor” element to it). We just are better at keeping separate from power, or at least official power.

Thanks for reading and for the thoughtful comments.

Very well written post and an interesting one! I enjoyed reading it. Thanks for sharing and congratulations for being on Freshly Pressed!

Thanks very much and I’m glad you enjoyed it!

You are most Welcome! Good Luck to your upcoming blogs 🙂

awesome analysis

Thanks!

Pingback: Do politicians cause famines? « Development / Skeptic

It’s frightening how similar it is where i am from – the hoarding, the nepotism, the family honor… Yet ours is in Europe (at least geographically, because Balkans are a region into itself… sigh.)

I have a friend from Macedonia who has said very similar things about her country. Corruption is everywhere, but I think it really becomes more rampant in places where people are or have been vulnerable.

In starting a blog about a small Canadian town, we are also prone to corruption, potentially. Unfortunately, here to things are swept under a rug while the locals remain silent. But we are no Afganistan. Interesting perspective. Enjoyed your article very much!

Thanks very much! Interesting how similar people can be despite being so different in other ways. Would love to hear some of your stories from your hometown!

Pingback: Saturday Link Round-Up 1 « Emilie Hardie

You’ve cleared many questions on this topic with this post. I understand your point about asian cultures and the value of their families. To me it looks like people should just about accept this situation, if that’s the way it is, I see no other alternative. If every leader is going to do the same then people die or are living in horrendous situations for no reason.

Or, you could invent a different political system, one that might fit the country’s lifestyle more. Longshot, in a way though. Maybe laws should be passed as to how many people of a similar family can be favoured?

Interesting…legislating and regulating nepotism. I’m not sure all the NATO countries who worked so hard to model the constitution after their own would approve, but I bet it’d be an interesting idea to the Afghans. Thanks for the food for thought!

A reblogué ceci sur difference propre and commented:

Je crains que le monde ne devienne comme l’Afghanistan.

Pingback: Brookings Fellow Sums Up Afghanistan Debacle In Two Short Paragraphs | Athens Report

Pingback: Brookings Fellow Sums Up Afghanistan Debacle In Two Short Paragraphs | ImpressiveNews

Pingback: Brookings Fellow Sums Up Afghanistan Debacle In Two Short Paragraphs | Wikisis

Pingback: Brookings Fellow Sums Up Afghanistan Debacle In Two Short Paragraphs | Finance News

Pingback: Brookings Fellow Sums Up Afghanistan Debacle In Two Short Paragraphs | The Las Angeles Times

Pingback: Brookings Fellow Sums Up Afghanistan Debacle In Two Short Paragraphs | New Yerk Times

Reblogged this on USAMA KADY.

Pingback: Brookings Fellow Sums Up Afghanistan Debacle In Two Short Paragraphs | The Business Defense News Network

A great insight into a situation we will never understand in America. You pay a steep price for learning and teaching that to us. Thanks for your effort. Stay safe, you are in my prayers.

Thank you very much. I think some people undervalue the word, but it is an honor for me to help us understand the world a little bit better.

Reblogged this on Grumpa Joe's Place and commented:

We all need to follow this blogger to receive a new education.

Very insightful. Almost educational in opening the readers’ eyes to a world that most know little about, except the occasional media-highlighted carnage and war. What we don’t seem to realise is that there are several million people who live there, most of whom are not terrorists or jihadis. They are ordinary people trying to live and care for their own, like the rest of us. While nepotism, cheating, bribery, hoarding, etc. may be part of the fabric they weave for themselves, can we at least help in getting violence out of their lives which, I believe, is the objective of the international forces stationed there.

Thanks very much. You captured my thoughts exactly…at the end of the day, people are people and there are usually reasons behind why they do what they do.

I really liked reading this blog. Thanks for writing it.

P.S. Want to learn how to make money with your blog? Go here to find out more. http://earncashathomeideas.com